Introduction

Electricity is one of the fundamental components on which modern society is built, but its principles are often ignored in everyday life. The handheld smartphone, the overhead ceiling fan that regulates the environmental conditions, and all the functional elements of the unit rely on carefully designed electrical circuits. The heart of these circuits is composed of resistors, or gadgets that are used to introduce a regulated resistance to the flow of electricity.

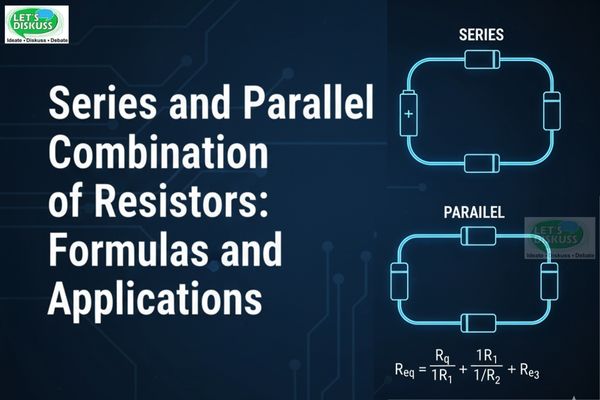

In real-world engineering usage, resistors are rarely used singly, but are fitted in series or parallel circuits depending upon the particular purpose of the circuit. The overall behaviour of these assemblies (especially the composite impedance to the source) is sensitive to the topology of these elements. The quantitative study of series/parallel networks of resistors, as a result, is essential to proper circuit modeling and circuit design.

This discussion explains the logical process of obtaining the identical resistances in a series and parallel system. The exposition follows the process of analytical deduction, and is accompanied by illustrative schematic diagrams, reminiscent of the textbook illustrations, and a conclusion where the results are tabulated, allowing the reader to re-establish the underlying principles in a rather brief and precise manner.

Understanding Resistor Combinations

Different arrangements of the use of various resistors are feasible in electrical circuits. The actual disposition of resistors has an influence on the behavior of current movement and the behavior of total resistance.

Two fundamental types of combinations are:

-

Series Connection – where resistors are connected end-to-end.

-

Parallel Connection – in which the resistors also share the common two nodes (connect together both ends).

In some cases, circuits also consist of an amalgamation of parallel and series arrangements, known as a series-parallel combination. Let's first study series and parallel circuits individually before proceeding with the mixed cases.

Why Do We Need to Combine Resistors?

Imagine you’re building a circuit, but you don’t have the exact resistor value you need. What do you do? Instead of giving up, you can combine two or more resistors to achieve the desired resistance.

Another reason is that resistors behave differently when arranged in series or parallel. In some circuits, you want the current to remain constant through all components (series). In others, you want devices to work independently, even if one fails (parallel).

Understanding how to combine resistors allows us to:

-

Simplify complicated circuits into manageable parts.

-

Calculate how the current and voltage will distribute.

-

Design systems that are safe and efficient.

With that context, let’s get into the details.

Resistors in Series

1. What is a Series Connection?

The resistors can be said to be in series when they are placed one right after the other; hence, the same current passes through all the elements. A good example is of water flowing through a pipe in a linear fashion. As more pieces of the pipe are added, the fluid has to flow through each section in the linear sequence. By this, in a series circuit, electronic charges are required to pass one resistor at a time.

In the Figure, two resistors, R1 and R2, are shown in series. The current entering the first resistor is exactly the same as the current leaving the last one.

A simple analogy is standing in a security line at an airport. You first pass through security check 1, then security check 2, and so on. The passenger (current) must go through each checkpoint in order.

2. Voltage in Series

The total voltage supplied by the source is divided across the resistors. Each resistor takes a portion of the voltage depending on its resistance. If V is the total voltage and the current is I, then:

V = V1 + V2 + V3 + ⋯ + Vn

Where V1 = IR1, V2 = IR2, and so on.

3. Equivalent Resistance in Series

The most useful result is that resistances simply add up:

Req = R1 + R2 + R3 + ⋯ + Rn

This makes series circuits very straightforward to analyze.

4. Example: Two Resistors in Series

Suppose R1=4Ω and R2=6Ω.

Req = 4+6 = 10Ω

If a 10 V battery is connected, the current is:

I = V/Req = 10/10 = 1A

The voltage drops are:

V1 = IR1 = 1×4 = 4V,

V2 = IR2 = 1×6 = 6V

So the total V = V1 + V2 = 10 V, as expected.

5. Example: Three Resistors in Series

In the Figure, three resistors R1, R2, and R3 are connected in series. If their values are 2 Ω, 3 Ω, and 5 Ω, then:

Req = 2 + 3 + 5 = 10 Ω

The principle remains the same, no matter how many resistors you add.

Resistors in Parallel

1. What Does “Parallel” Mean?

Resistors are in parallel when both ends of each resistor are connected together, as shown in the Figure. In this case, each resistor experiences the same voltage, but the current splits into branches.

Think of parallel as water pipes: you can open two or three taps from the same water source. Each tap gets the same pressure (voltage), but the water flow (current) divides.

2. Current in Parallel

The total current from the source equals the sum of currents through each branch:

I = I1 + I2 + I3 + ⋯ + In

3. Equivalent Resistance in Parallel

The reciprocal of the equivalent resistance equals the sum of reciprocals of individual resistances:

1/Req = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3 + ⋯ + 1/Rn

For just two resistors:

Req = (R1R2) / (R1+R2)

4. Example: Two Resistors in Parallel

Suppose R1=6 Ω and R2=3 Ω.

Req = (6×3) / (6+3) = 18/9 = 2 Ω

Notice that the equivalent resistance is smaller than the smallest resistor. This is always true for parallel combinations.

5. Example: Three Resistors in Parallel

In the Figure, three resistors R1, R2, and R3 are connected in parallel. Let’s take R1=4 Ω, R2=6 Ω, R3=12 Ω.

1 / Req = 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/12 = (3+2+1)/12 = 6/12 = 1/2

Therefore, Req = 2 Ω

6. General Rule

Adding more resistors in parallel always reduces the total resistance. That’s why household wiring is designed in parallel—to ensure each appliance gets the full voltage supply, while the circuit can handle multiple devices at once.

Series-Parallel Combination

Real circuits rarely have only series or only parallel arrangements. More often, they are a combination of both.

1. Example: Resistors in Parallel + Series

Consider three resistors R1, R2, and R3 as in the Figure. Here, R2 and R3 are in parallel, and their equivalent resistance is in series with R1.

Step 1: Find the equivalent resistance of the parallel pair R2 and R3.

Req23 = (R2 R3) / (R2 + R3)

Step 2: Find the total equivalent resistance by adding R1 and Req23 in series.

Req123 = R1 + Req23

Example:

Let R1=5 Ω, R2=10 Ω, R3=20 Ω.

Req23 = (10 × 20) / (10 + 20) = 200 / 30 ≈ 6.67 Ω

Req123 = 5 + 6.67 = 11.67 Ω

This technique can be extended to much more complex circuits by reducing them step by step.

Applications of Series and Parallel Resistors

1. Current and Voltage Behavior

-

Series circuits: Current is constant, voltage divides.

-

Parallel circuits: Voltage is constant, current divides.

2. Real-Life Uses

-

Series: Voltage divider networks, vintage Christmas light assemblies, and other applications where one current flow is required to go through each element use series configurations.

-

Parallel: Parallel is employed in residential wiring, car electrical systems, and power distribution networks, where reliability of the system and constant supply of voltage are the most important.

3. Safety Considerations

In homes, parallel wiring is made so that when a bulb breaks, the rest of the lights will not go off. In a series wiring in the household, the failure of a single component to operate, e.g., the lighting and fan system, would stop the operation of the entire circuit, demonstrating the practical benefits of the parallel system in safety.

Table 1: Comparison of Series and Parallel Resistors

| Feature | Series Connection | Parallel Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Current | Same through all resistors | Divides among resistors |

| Voltage | Divided across resistors | Same across each resistor |

| Equivalent Resistance Rule | Req=R1+R2+⋯+Rn | 1/Req=1/R1+⋯+1/Rn |

| Effect of Adding Resistors | Increases total resistance | Decreases total resistance |

| Practical Example | Old decorative lights, series testing | Household wiring, power grids |

Table 2: Quick Reference Formulas

| Case | Formula for Req | Key Point |

|---|---|---|

| Two resistors in series | Req=R1+R2 | Resistances add directly |

| Three resistors in series | Req=R1+R2+R3 | Same current in all |

| n resistors in series | Req=R1+R2+⋯+Rn | General rule |

| Two resistors in parallel | Req=R1R2/R1+R2 | The result is smaller than the smallest resistor |

| Three resistors in parallel | 1/Req=1/R1+1/R2+1/R3 | Voltage is the same across each branch |

| n resistors in parallel | 1/Req=1/R1+⋯+1/Rn | Extends to many resistors |

Conclusion

The pattern of connections between resistive elements, be it in series, in parallel, or in a combination of the two, has a direct effect on how current and voltage are distributed in an electrical network. In series connections, resistances are added, and the current flowing through all components is identical. In a parallel setup, the potential difference is the same on every branch with the current being split; thus, the net resistance becomes lower.

The detailed knowledge of these principles allows for reducing complex networks of resistors to equivalent circuits, and thus designing systems that can be safe and efficient. Since the light in the home is connected to an integrated circuit in the portable device, the new behavior of the resistor interplays with the basis of the operation of virtually all of the electrical infrastructure.