Introduction

Electricity is nearly ubiquitous in modern-day technological applications, including handheld communication gadgets, as well as car propulsion systems. However, the basic building block of these applications is the electrochemical cell. The proper understanding of cell behavior requires the analysis of the two key parameters, electromotive force (EMF) and internal resistance.

This discussion will set out to define the terms EMF and internal resistance, explain their relevance, and evaluate their effect on the practical electrochemical cell functionality. Also, the analysis will provide succinct mathematical representations that can be used to assess electrical networks that include such cells. Let us proceed.

Understanding the Cell

1. What is a Cell?

At its core, a cell is a device designed to maintain a steady current in an electric circuit. It does this by using chemical reactions that occur within an electrolyte solution. These reactions allow charges to move between two electrodes—one positive (P) and one negative (N).

Figure (a) shows the schematic diagram of the concerned cell. The electrodes are placed into the electrolyte, and electrical contacts are made to the electrode P (positive) and N (negative). The distance between the electrodes has been exaggerated to make the figure easy to understand, but it helps in the visualization of the charge migration within the electrolyte.

2. Construction of a Cell

-

Positive electrode (P): Has a potential difference Vp relative to the solution around it.

-

Negative electrode (N): Develops a potential difference Vn relative to its adjacent electrolyte.

When no current flows, the electrolyte maintains a uniform potential. But once a circuit is completed, charges begin to flow, and a steady current is established.

Electromotive Force (EMF) of a Cell

1. Definition

The electromotive force (EMF) of a cell, denoted by ε, is the total potential difference between the positive and negative terminals of the cell when no current flows through it.

It is important to note that although the word “force” is used, EMF is not actually a physical force—it is a potential difference. The term persists mainly due to historical usage.

2. Expression for EMF

From the Figure, we can see that:

ε = Vp + Vn

Here:

-

Vp is the potential difference between the positive electrode and the electrolyte.

-

Vn is the potential difference between the electrolyte and the negative electrode.

Thus, EMF is essentially the energy supplied by the cell per unit charge when no current flows.

Internal Resistance of a Cell

1. What is Internal Resistance?

When current begins to flow, the electrolyte inside the cell itself offers some opposition to the movement of charges. This is called the internal resistance, denoted by r.

Think of internal resistance as a hidden resistor inside every cell. It’s unavoidable, and it always reduces the efficiency of the cell.

2. Why Internal Resistance Matters

-

If internal resistance is small, the cell delivers more usable voltage to the external circuit.

-

If internal resistance is large, a significant part of the EMF is wasted inside the cell, reducing the external voltage.

Potential Difference Across a Cell

1. Open Circuit (No Current Flowing)

When no current flows through the cell (I=0), the potential difference between its terminals (P and N) is equal to the EMF:

V = ε

This is why EMF is often measured when the circuit is open.

2. Closed Circuit (Current Flowing)

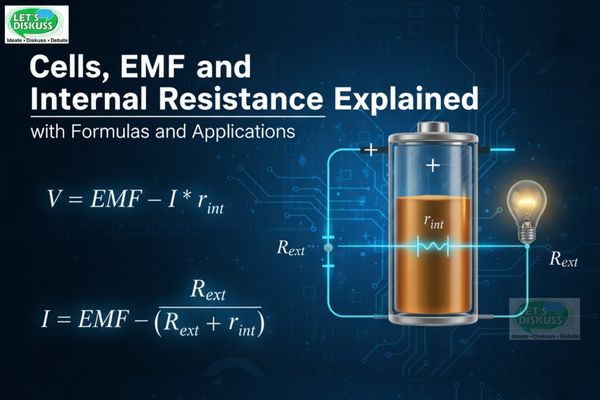

When current I flows through the circuit, the actual potential difference across the terminals drops because part of the EMF is lost in overcoming the internal resistance.

V = ε − Ir

Here:

-

V = terminal voltage (what you measure with a voltmeter when the circuit is closed),

-

Ir = voltage drop inside the cell due to internal resistance.

This explains why your batteries often show a slightly lower voltage when powering a device than when measured at rest.

Deriving the Current in the Circuit

Consider a resistor R connected across the terminals of the cell (Figure a).

From Ohm’s law, the potential difference across R is:

V = IR

But we also know from the earlier relation that:

V = ε − Ir

Equating the two gives:

IR = ε − Ir

Rearranging,

I = ε / (R + r)

This simple but powerful expression tells us that the current in the circuit depends on both the external resistance R and the internal resistance r.

Maximum Current from a Cell

1. Condition for Maximum Current

The maximum current that a cell can deliver occurs when the external resistance is zero (R=0). In this case,

Imax = ε / r

2. Practical Limitation

In practice, however, drawing maximum current is never recommended. Doing so can permanently damage the cell because it causes rapid heating, chemical degradation, or even leakage in real batteries. Manufacturers specify a safe current limit far below Imax.

Real-Life Impact of Internal Resistance

1. Why Batteries Die Faster Under Heavy Load

When you connect a high-power device to a battery, the current drawn increases. Since the internal drop Ir also increases, the external voltage available to the device falls. This is why gadgets sometimes shut off suddenly, even though the battery isn’t fully drained.

2. Different Cells, Different Resistances

-

Dry cells (like AA batteries) have relatively high internal resistance.

-

Lead-acid batteries used in cars have very low internal resistance, allowing them to deliver high currents for starting engines.

-

Lithium-ion batteries (used in phones) balance low internal resistance with compact size.

Applications and Importance

1. Voltage Drop Considerations

Whenever we use a battery in practical circuits, we must account for the fact that the terminal voltage is less than the EMF when current flows. Engineers use this concept when designing circuits to ensure stable performance.

2. Internal Resistance in Testing and Design

Battery testers and power management systems in electronic devices measure internal resistance to estimate the health and remaining life of a battery. A higher internal resistance usually means the battery is aging or degrading.

Summary of Key Formulas

-

EMF (Open Circuit):

ε = Vp + Vn

-

Terminal Voltage (Closed Circuit):

V = ε − Ir

-

Current in Circuit:

I = ε / (R + r)

-

Maximum Current:

Imax = ε / r

Conclusion

The physics that controls the operation of electrochemical cells is exciting and strong, even though they might seem to be tiny and straightforward. The principles of electromotive force and internal resistance give the reason why the actual batteries are never able to produce their theoretical voltage and why their behavior varies with load.

These principles are the same in the case of AA batteries of everyday size, and in the case of the huge lead-acid cell used to drive backup systems. Learning about electromotive force and internal resistance, not only do we know how batteries operate, but we can also learn how to make better use of them in our day-to-day lives.

Thus, next time your phone battery drops to 0% without warning, or your flashlight is dwindling, then bear in mind - it is never only about charge, it is about internal resistance working in its silent background.