Introduction

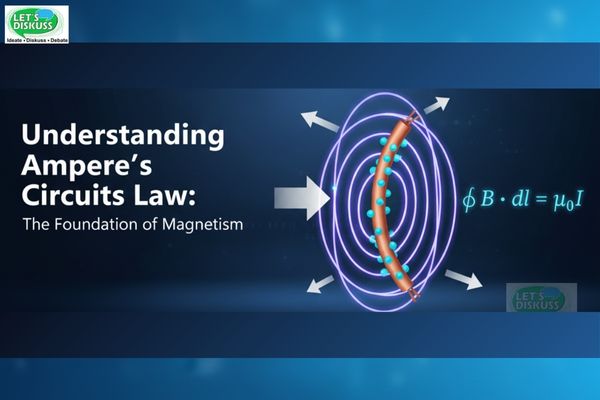

Ampere's Law of Circuits is also a law of electromagnetism that defines the Ampere law as it relates the current flowing through each conductor in a circuit to the resulting magnetic field so that researchers and engineers can analyze and design from the simplest electromagnets and wound resolvers through highly complex electric motors and other devices.

Comprehension of Ampere's Law is crucial for understanding the underlying connection between electricity and magnetism that is the foundation for numerous modern technologies. This article will examine its history, mathematical statement, experimental usage, and derivations of Ampere's Law, supported by relevant numbers and illustrations.

Historical Background and Significance

This law is named after two distinguished French physicists and mathematicians of the 19th century, André-Marie Ampère, who is the origin of the relationship currently called Ampere Law, which summarizes the magnetic consequences of the electric currents. The works of Ampere were a fundamental basis in the process of producing electricity and magnetism, which finally led to the equations of neoclassical electromagnetism done by Maxwell.

In early experiments, Ampere demonstrated the presence of forces of a magnetic nature between conductors with electric currents flowing on them and later attempted to develop a quantitative explanation of the occurrence of this interaction. The development of his theory led to the eponymous law, and it continues to form a foundation of electromagnetic theory.

Understanding the Concept of Magnetic Fields

Before getting involved in the mathematical formalism that follows, one will need to have a systematic understanding of what magnetic fields mean. A magnetic field is a type of vector field that represents the magnetic effect of electrical currents and magnetic substances. This area works on both the moving electric charges and the magnetic dipole.

Normally, magnetic field lines are used to portray the magnetic field. The directional qualities of the magnetic force are expressed through these lines and appear in the form of closed loops surrounding conductors carrying electric current, as is the case with Fig. 1.

In this figure, the figure of concentric circles around a straight wire is used to mark the lines of the magnetic fields, which represent the field based on the right-hand rule.

The Mathematical Formulation of Ampere’s Law

Ampere’s Law connects the magnetic field B around a closed loop to the total current passing through the loop. It has two equivalent forms: the integral form, which is often used for practical calculations, and the differential form, which provides a local description of the magnetic field.

4.1 Integral Form of Ampere’s Law

The integral form of Ampere’s Law is expressed as:

∮CB ⋅ dl = μ0 Ienc

Where:

- ∮C denotes the line integral around a closed path C,

- B is the magnetic flux density,

- dl is an infinitesimal element of the path C,

- μ0 is the permeability of free space (4π×10−7 H/m),

- Ienc is the total current enclosed by the path.

This law states that the line integral of the magnetic field around any closed loop equals μ0 times the current passing through the loop.

Fig. 2 illustrates a typical application: a closed circular path around a straight wire.

In this figure, the magnetic field lines are concentric circles, and the path C is a circle of radius r centered on the wire.

4.2 Differential Form of Ampere's Law

The differential form relates the curl of the magnetic field to the current density:

∇ × B = μ0J

Where:

- ∇ × B is the curl of the magnetic field,

- J is the current density vector.

This form tells us that the local rotation of the magnetic field at a point is proportional to the current density at that point.

Applying Ampere's Law: Practical Examples

Ampere's Law is also useful for determining B fields in symmetry problems. We'll examine a few typical configurations.

5.1 Magnetic Field of a Long Straight Wire

Let's consider a non-circular conducting wire that carries a current I, as described in Fig. 3. In finding the field at a distance r from the conductor, we place a circular trajectory of radius r around the wire.

Fig. 3: Magnetic field around a long straight wire

Applying Ampere's Law:

∮C B ⋅ dl = B ∮C dl = B(2πr)

Since the magnetic field is tangent to the circle and has constant magnitude B:

B(2πr) = μ0I

Solving for B:

B = μ0I/2πr

This expression shows that the magnetic field decreases with distance from the wire and encircles the wire according to the right-hand rule.

5.2 Magnetic Field of a Circular Loop

Take a circular loop of radius R with current I flowing through it. To compute the field at a point on the axis of this loop, the Biot–Savart Law is applicable; but for computing the field at the centre of the loop, Ampere's Law can be used (see Fig. 4.17).

Fig. 4.17: Magnetic field at the center of a circular current loop

Applying symmetry and Ampere's Law, the magnetic field at the center is:

B = μ0I/2R

which is derived directly from the integral form, considering the magnetic field contributions from all current elements.

The Right-Hand Rule and Its Significance

Determining the direction of the magnetic field is facilitated by the right-hand rule. For a current-carrying conductor:

- Point the thumb in the direction of conventional current (I)

- Curl the fingers around the conductor

- The fingers point in the direction of the magnetic field lines

This rule is visually summarized in Fig. 4.18.

Examples and Calculations

Let's work through specific examples to reinforce the concepts.

7.1 Example 1: Magnetic Field at the Center of a Circular Loop

Given: A circular loop of radius R=0.1 m carries a current I=5 A.

Find: The magnetic field at the center of the loop.

Solution: Using the formula:

B = μ0I/2R

Insert values:

B = (4π×10−7)×5/2×0.1 = (4π×10−7)×5/0.2

B ≈ 6.2832×10−6/0.2 = 3.1416×10−5 T

The magnetic field at the center is approximately 31.4 μT.

7.2 Example 2: Magnetic Field at a Point Outside a Solenoid

Given: A long solenoid with N=1000 turns, length L=1 m, carrying current I=2 A.

Find: The magnetic field at the center of the solenoid.

Solution: The magnetic field inside an ideal solenoid is given by:

B = μ0 × N/L × I

Calculate:

B = (4π×10−7)×1000/1×2≈8×10−4 T

which is 0.8 mT.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

While Ampere’s Law is powerful, it has limitations:

- It is most straightforward to apply in cases of high symmetry (cylindrical, planar, spherical).

- In complex geometries with non-uniform currents, the law can be difficult to apply directly.

- The law assumes steady currents; in dynamic situations, Maxwell’s correction (displacement current) must be included.

Ampere’s Law in Modern Electromagnetism

Ampere's Law in contemporary physics has turned out to be a constitutive and integral component of Maxwell's equations that underpin all classical behaviors of electromagnets. The law is also crucial in designing and developing various electrical devices, such as transformers, inductors, and electromagnets, and in comprehending the flux of magnets within electrical systems.

In the presence of changing electric fields, the law is modified to include the displacement current term:

∇×B=μ0J+μ0ϵ0×∂E/∂t

This extension is vital for understanding electromagnetic waves and high-frequency applications.

Conclusion

The Circuital Law by Ampere has introduced a basic correspondence between the magnetic fields and electric currents. It can be mathematically formulated to allow an accurate calculation of magnetic fields in symmetric configurations, giving the basis of most modern electromagnetism and electrical engineering.

Since the elementary magnetic field around a conductor to the complex action of inductors and electromagnets, Ampere's Law remains an invaluable tool for understanding and utilizing the magnetic phenomena.