Introduction

Have you ever thought of why it is better when you put stuff between the plates of a capacitor? Here, I will demonstrate the effect that dielectrics have on capacitors in terms of strength and how to supercombine them in a real circuit. To be completely honest, capacitors are all around you; you can use a charger for your phone, the sound system in your headphones, or your name it. A dielectric addition or connection of additional capacitors, in effect, can completely alter the operation. I will make it easy by doing it step by step using simple examples and a few straightforward equations so that even when you are not a science genius, you will be able to follow.

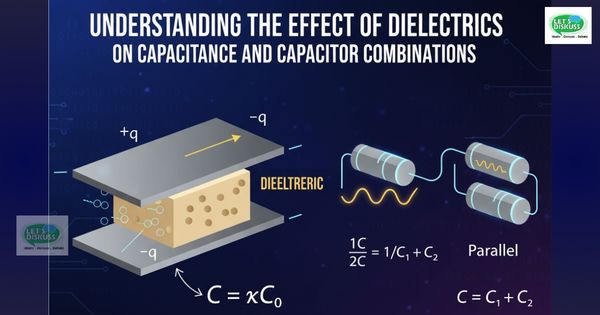

What Are Capacitors and Dielectrics?

Dielectrics are insulating materials that are used to fill the space between plates to enhance the efficiency of capacitors that store electricity. A capacitor is made up of two metal plates with a gap between them. When you induce a voltage, you induce a positive charge in one plate and a negative charge in the other, and the electric field between them stores the energy. A dielectric is something such as glass, plastic, or even air, but typically, a solid or liquid insulator. It does not carry electricity, but polarises in the field, thus allowing the capacitor to store a higher amount of charge without raising the voltage or altering the size of the plate.

Why This Matters for Electronics

Being aware of these concepts will enable you to design better circuits, simple or sophisticated power supplies. When you are making something, having information about how the dielectrics increase capacitance allows you to use smaller components with the same effect and save space and money. Mixing capacitors allows you to adjust values that you cannot simply buy right out of the box. It is nitty-gritty to hobbyists, engineers, or to anyone who is curious about how gadgets operate internally.

The Effect of Dielectrics on Capacitance

Dielectrics completely transform the way the capacitors will behave because they slice the electric field and allow these capacitors to hold higher amounts of charge even without coming into contact with the plates. With a simple system in the absence of a dielectric, the electric field is too strong, and the capacitor cannot sustain much until it ruptures. Put a dielectric in it, and it destroys that field indoors so that you can stuff more charge on the plates at a given voltage. This is due to the fact that the molecules of the dielectric become aligned with the field and form their own antagonistic field.

1. Basics of Dielectrics in a Parallel-Plate Capacitor

Start with a vacuum-filled capacitor: the capacitance is C = ε₀A/d with ε₀ being the vacuum permittivity, A the area of plates, and d the plate separation. This equation is a direct result of Gauss's law of electricity. ε₀ is approximately 8.85 × 10^{-12} F/m, and it is basically what tells us the way the electric fields propagate through space. In the case of a real capacitor with a capacity of a specific area A and an opening of a specific distance d, the base capacitance is obtained. In reality, though, we tend to put in there a dielectric to increase C.

When a dielectric is added, the capacitance becomes C = κ ε₀ A/d, and the dielectric constant 0 is greater than 1. For example, if κ is 4 for a material like bakelite, your capacitance quadruples. That's huge for compact designs. Parallel plates are given as examples in the book, and they refer to the fact that the dielectric must fill the gap entirely or the equation will not work with it.

2. How Dielectrics Polarize and Reduce the Field

When you insert a dielectric, it polarizes, creating induced charges that oppose the external field, effectively lowering the net field to E = (σ - σ_p)/ε₀. Here, σ is the free charge density on the plates, and σ_p is the induced polarization charge on the dielectric surfaces. The polarization P is the dipole moment per unit volume, and it's proportional to the electric field: P = χ_e ε₀ E, where χ_e is the electric susceptibility.

This polarization happens because the dielectric's atoms or molecules shift slightly in the field. Positive parts move one way, negative the other, creating tiny dipoles. At the surfaces, this leads to bound charges that reduce the overall field inside. The result? The voltage V = Ed drops for the same charge, or equivalently, you can add more charge for the same V. The excerpts describe this with vectors: the electric field E points from positive to negative plate, and P aligns with it, leading to σ_p = P · n̂ at the surfaces.

3. The Dielectric Constant (κ) and Its Impact

The dielectric constant κ > 1 multiplies the vacuum capacitance, so C = κ ε₀ A/d, making the capacitor store more charge for the same voltage. κ measures how much the material reduces the field compared to the vacuum. For air, it's about 1.0006, nearly a vacuum. For water, it's around 80, which is why water capacitors aren't common—they'd leak. Common dielectrics like mica (κ ≈ 6) or ceramics (up to thousands) are used in real caps.

From the physics side, κ = ε / ε₀, where ε is the permittivity of the material. This ties back to D = ε E, the electric displacement. In a vacuum, D = ε₀ E, but with a dielectric, D stays tied to free charges while E drops. The ratio D/E = ε shows the enhancement. Experiments confirm this: insert a slab, measure the new C, and κ = C / C_0, where C_0 is the vacuum value.

4. Permittivity and Electric Susceptibility

Permittivity ε = κ ε₀ measures the medium's response, while susceptibility χ_e = κ - 1 quantifies polarization strength relative to the field. ε tells you how easily the material permits an electric field through it. Lower ε means a stronger field for the same D, but in dielectrics, it's higher.

χ_e links to how polarizable the material is. For linear dielectrics, P = χ_e ε₀ E, so ε = ε₀ (1 + χ_e), hence κ = 1 + χ_e. This is key for understanding non-vacuum media. The excerpts derive this from the displacement: D = ε₀ E + P = ε₀ (1 + χ_e) E. For most materials at room temperature, this holds until fields get extremely strong.

5. Electric Displacement (D) Field

The displacement D = ε₀ E + P relates directly to free charge, helping explain why dielectrics boost overall performance without altering free charges. In Gauss's law, ∇ · D = ρ_free, where ρ_free is the free charge density. This ignores bound charges from polarization, which are accounted for in P.

For a capacitor, D = σ n̂, constant and equal to the free charge density. Since E = D / ε, the field drops by κ, and V drops too, allowing more charge Q = C V with higher C. This vector approach from the texts shows D, E, and P are parallel in isotropic materials. It's a clean way to handle boundaries and interfaces.

Combining Capacitors: Series and Parallel Configurations

Combining capacitors lets you tailor total capacitance to your needs, whether adding up values or dividing voltage. Often, you don't have the exact capacitance you need, so you wire multiples together. Series and parallel are the basics, like resistors but inverted for capacitance.

1. Why Combine Capacitors?

In circuits, series setups share charge while parallel ones share voltage, allowing flexible designs for batteries, filters, or energy storage. The series is great for handling high voltages, as each cap takes a share. Parallel boosts total storage for the same voltage.

2. Capacitors in Series

For two capacitors in series, the total voltage V = V₁ + V₂ = Q (1/C₁ + 1/C₂), so the equivalent capacitance is 1/C = 1/C₁ + 1/C₂. Here, charge Q is the same on each, since no current flows through the dielectric. The excerpts illustrate this with diagrams: plates connected such that the middle ones cancel charges, leaving net Q on ends.

This means the effective C is less than the smallest individual. For example, two 10 μF in series give 5 μF. Useful for safety in high-voltage apps.

(a). Extending to Multiple Capacitors

This formula generalizes to n capacitors: 1/C = Σ (1/C_i), ensuring charge conservation across the chain. For three caps, say 2 μF, 3 μF, 6 μF: 1/C = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/6 = 1, so C=1 μF. It's like the harmonic mean.

(b). Real-World Example: Voltage Division

In a series pair with equal charges Q, each sees a portion of the total voltage, useful for stepping down potentials safely. If C1 = 2 C2, V1 = Q/C1 = (1/2) (Q/C2) = (1/2) V2, so larger C takes less voltage drop. This divides the voltage proportionally to 1/C.

3. Capacitors in Parallel

In parallel, the total charge Q = Q₁ + Q₂ = C₁ V + C₂ V, so the equivalent capacitance C = C₁ + C₂, summing up for higher storage. Voltage V is the same across all, and charges add. Diagrams show plates connected directly to the source.

For example, two 10 μF in parallel give 20 μF. Perfect for increasing capacity in power smoothing.

(a). Scaling to n Capacitors

For multiple units, C = Σ C_i, with shared voltage across all, ideal for increasing overall capacity without complexity. n identical C's give nC total. No limit theoretically, but practically, watch for leakage.

(b). Practical Application: Charge Sharing

Parallel combos shine in power supplies where you need to handle more current by distributing the load evenly. In audio amps, parallel caps filter noise better by lowering ESR.

Advanced Insights: Dielectrics in Combinations

Integrating dielectrics into series or parallel setups can fine-tune circuit behavior even further. Dielectrics aren't just for single caps; they affect combos too.

1. Effects in Series Configurations

Dielectrics in series capacitors adjust effective κ based on thicknesses, like treating slabs as stacked media. If two dielectrics are in one gap, it's like series caps: 1/C = d1/(ε1 A) + d2/(ε2 A). Effective κ = (d1 + d2) / (d1/κ1 + d2/κ2).

2. Parallel Dielectric Mixtures

The sensation of having parallel capacitors is similar to that of mixing dielectrics side-by-side, except that you simply average the capacitances depending on the size of each area. For areas A1 and A2, C = ε1 A1 / d + ε2 A2 / d. Effective κ = (κ1 A1 + κ2 A2)/A.

Conclusion

Mastering dielectrics and capacitor combinations unlocks efficient, reliable electronics—next time you're prototyping, try tweaking these for better results. We've covered the basics from polarization to practical wiring, drawing from standard physics explanations. Whether you're fixing a gadget or designing one, these ideas apply directly.