Introduction

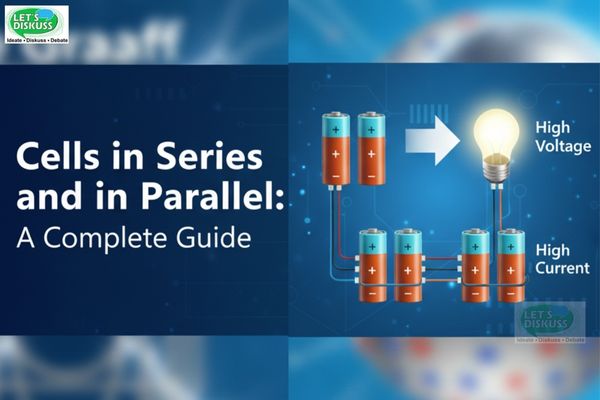

The essence of almost all the electrical and electronic appliances that are widely used today is electric cells. Cells are everywhere, whether it is the small AA batteries used in a television remote control or the large battery systems used to keep a data center online even when power is unavailable. However, a single cell often cannot provide the voltage or current required by practical applications, and so a series and parallel combination of cells is often required.

Just like resistors, cells can be combined in series and parallel to form the desired electrical characteristics. Cells can be stacked to increase voltage, increase current-carrying capacity, or increase the general battery life, so these combinations are imperative in effective power management. In the article, the principles of the arrangement of cells in series and parallel, rigorously treats the resulting electrical parameters mathematically and are shown to be applicable to real-world situations without getting lost in cryptic jargon.

Understanding Cell Combinations

Before diving into the math and figures, let’s build some intuition. Why would we even want to combine cells?

-

To increase voltage: A single cell (like a dry cell) usually has a voltage of about 1.5 V. If your device needs 9 V, you need six such cells connected in series.

-

To increase current capacity: Some devices, like inverters or car batteries, need a lot of current. In such cases, cells are connected in parallel to supply enough power.

-

To balance power and durability: In practical applications, designers often combine series and parallel connections to optimize both voltage and current.

Now that the “why” is clear, let’s move on to the “how.”

Cells in Series

Concept of Series Connection

When cells are connected in series, the positive terminal of one cell is connected to the negative terminal of the next. The remaining free terminals (one positive, one negative) act as the output of the combination. This arrangement is shown in Fig. 1.

Series connection is often used when we need a higher voltage than what a single cell can provide. For example, stacking four 1.5 V cells gives us a 6 V battery.

Potential Difference Across Cells in Series

Let us consider two cells in series with emfs ε1 and ε2, and internal resistances r1 and r2. Suppose a current I flows through the series circuit.

From the diagram (Fig. 1), the potential difference between points A and C is:

VAC = (ε1 + ε2) – I(r1 + r2)

This equation tells us that the total voltage is simply the sum of the individual emfs, minus the voltage lost due to internal resistances.

Equivalent Cell in Series

If we replace the series combination with a single equivalent cell, its emf and internal resistance are:

εeq = ε1 + ε2

req = r1 + r2

This makes sense—voltage adds up, and resistances also add because the same current flows through all the cells.

Special Case: Opposite Polarity Connection

The consequence of this is that when you take not the negative terminal of one cell and join it to the positive terminal of the other, but the positive terminal of one cell and join it to the positive terminal of the other. The cells are antagonistic to each other in this configuration. Equivalent electromotive force (emf) is:

εeq = ε1 – ε2 (ε1 > ε2)

This arrangement is less common in practice, but it’s useful in cases where we want to fine-tune the output voltage.

General Rule for Series

The rules can now be generalized:

-

The equivalent emf of n cells in series = the sum of all individual emfs.

εeq = ε1 + ε2 + ⋯ + εn

-

The equivalent internal resistance of n cells in series = the sum of all internal resistances.

req = r1 + r2 + ⋯ + rn

So, in short: Series = Voltage boost, Resistance adds.

Cells in Parallel

Concept of Parallel Connection

The current section examines parallel associations. In this type of arrangement, the positive terminals of the individual cells in the arrangement are all connected, and so are the negative terminals. The final set of connections is shown in Figure 2.

The parallel connections are beneficial in cases when one has to increase capacity but leave the voltage constant. To take the case of a vehicular battery system, which is basically a large collection of smaller cells joined together in parallel.

Current Distribution in Parallel Cells

In a parallel arrangement, the overall current is divided between the individual branches. To represent the current due to the first cell by I1 and the second by I2, the total current supplied may be represented by:

I = I1 + I2

This is just the principle of conservation of charge—whatever current flows into a junction must flow out.

Potential Difference Across Parallel Cells

Let’s derive the expression for the potential difference across parallel cells.

For two cells with emfs ε1, ε2 and internal resistances r1, r2, the combined voltage at the output can be shown as:

V = (ε1r2 + ε2r1)/(r1 + r2) – I(r1r2)/(r1 + r2)

This equation is used to show how the parallel connection balances the electromotive forces and internal resistances to produce the same terminal voltage.

Equivalent Cell in Parallel

We can now define an equivalent emf and internal resistance for parallel cells:

εeq = (ε1r2 + ε2r1)/(r1 + r2)

req = (r1r2)/(r1 + r2)

It would be seen that, in this case, the corresponding internal resistance is always less than any of the individual resistances, and this is the reason why, when a stronger current flow is necessary, parallel structures are employed.

Simplified Relations for n Cells in Parallel

For n cells in parallel, the rules can be generalized:

-

Equivalent resistance:

1/req = 1/r1 + 1/r2 + ⋯ + 1/rn

-

Equivalent emf:

εeq/req = ε1/r1 + ε2/r2 + ⋯ + εn/rn

So, in short: Parallel = Current boost, Resistance decreases.

Comparison Between Series and Parallel Cells

| Aspect | Series Combination | Parallel Combination |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage | Adds up (ε = ε₁ + ε₂ + …) | Same as one cell |

| Current Capacity | Same as one cell | Increases with more cells |

| Internal Resistance | Adds up (r = r₁ + r₂ + …) | Decreases (1/r = 1/r₁ + 1/r₂ + …) |

| Practical Use | When high voltage is needed | When high current or longer battery life is needed |

| Example | Torchlight battery, inverter battery banks | Car batteries, UPS systems |

This table makes it clear: use series when you need more voltage, and parallel when you need more current.

Applications in Real Life

Cells are combined in specific ways depending on the requirement:

-

Series connection:

-

Torchlights and flashlights use multiple cells in series to provide a higher voltage.

-

Inverters and solar power systems use series cells to reach the voltage needed for operation.

-

-

Parallel connection:

-

Car batteries are designed with parallel connections to supply large amounts of current.

-

Backup systems and power banks use parallel combinations to extend battery life.

-

-

Series-parallel combinations:

-

Laptops, electric vehicles, and renewable energy storage systems often use a hybrid of both series and parallel connections. This provides both the required voltage and the necessary current capacity.

-

Conclusion

The basic building blocks of electrical circuits are the cells; how these cells are connected to each other, be it in series or in parallel, defines the overall performance of the system.

-

The terminal voltages of the constituent cells add in line with their connection in series, but so does the cumulative internal resistance.

-

Parallel connection, on the other hand, leads to more aggregate current-carrying capacity and less equivalent internal resistance.

An overall understanding of these principles, coupled with the expressions of analysis shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, can provide the engineer and students with the tools they need to create efficient and reliable circuits. The series and parallel cell configurations are all used, whether the device is a handheld torch, an uninterruptible power supply, or an electric vehicle.