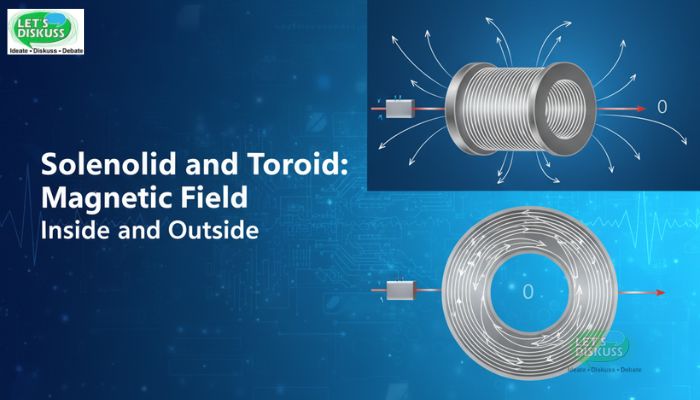

Magnetic fields caused by current form the basic premise of a wide range of electrical devices. One of the simplest but most powerful systems used to generate powerful and manageable magnetic fields is the solenoid and the toroid. Both machines take advantage of the law of Ampere under highly symmetrical conditions; the first, in its extended cylindrical version, would give a nearly spatially homogeneous magnetic field, and the second would keep the field localized to the circular core of the machine.

In the following section, we discuss, in some detail, the structural properties, dynamic behavior of such systems, and derivation of the magnetic fields, as shown in the Figures.

The Solenoid

1. Structure and Working Principle

A solenoid is a long coil of insulated wire, wound in a helical shape. The rotation of the coil can be modeled as a circular current loop, and the resulting cumulative magnetic field caused by the solenoid can be seen as the vectorial addition of that created by every turn. The passage of an electric current I through the solenoid creates a small magnetic field when the solenoid finishes a turn; the net magnetic field in the solenoid is this field added together with the magnetic field created by the previous turn.

When the length of the solenoid, L, is much larger than the radius r, then the device can be viewed as a long solenoid. Within the frame of this approximation, the magnetic field inside the solenoid is effectively homogeneous and parallel to the solenoid axis, and the magnetic field outside the solenoid is very small.

Solenoids find various applications in practice, in such devices as television sets, electromagnetic relays, magnetic sensors, and magnetic sensors in scientific equipment such as synchrotrons, where it is necessary to provide intense and easily manipulated magnetic fields.

2. Magnetic Field of a Finite Solenoid

In Figure 1, the magnetic field lines of a finite solenoid are illustrated. Only one section is shown in the subfigure 1(a) in the interest of clarity. Currents flowing in opposite directions on the adjacent sides, on the turns of successive windings, cause mutually opposite external field components to be cancelled.

The magnetic field lines are packed with each other and run parallel, a characteristic of a strong, spatially homogeneous field, inside the solenoid. Beyond the exterior of the solenoid, however, the lines of the field separate and become significantly smaller.

The entire solenoid is shown in subfigure 1(b). In an interior midpoint represented as P, the magnetic field is powerful and uniform, and perpendicular to the axis of the solenoid. At some exterior midpoint, denoted Q, the field is significantly weaker and oriented along the axis, but the components transversal to that axis are insignificant.

The longer the axial length of the solenoid, the closer the system is to an idealised infinite solenoid, where the outside magnetic field is virtually zero.

3. Ideal Solenoid Approximation

An ideal solenoid assumes that:

-

The solenoid is infinitely long.

-

The windings are closely spaced.

-

The field outside is zero.

-

The field inside is uniform and parallel to the axis.

Under these conditions, the solenoid behaves like a uniform magnetic field region—a useful approximation for both theory and applications.

Figure 2 represents this ideal case and introduces Ampere's loop used to derive the field inside.

Magnetic Field Inside a Long Solenoid

To calculate the magnetic field inside a long solenoid, we apply Ampere's circuital law:

∮B⋅dl=μ0Ienc

where

Ienc = total current enclosed by the Amperian loop, and

μ0 = permeability of free space.

1. Choice of Amperian Loop

We consider a rectangular Amperian loop abcd, as shown in Fig. 2, such that:

-

The side ab lies inside the solenoid and is parallel to its axis.

-

The side cd lies outside, where the magnetic field is approximately zero.

-

The sides bc and da are perpendicular to the field and therefore contribute nothing to the integral.

Since only the segment ab lies within the region of the significant field:

∮B⋅dl=B×L

where L is the length of the solenoid section considered.

2. Current Enclosed

Let

n = number of turns per unit length of the solenoid.

Then, in length L, the total number of turns is nL.

Each turn carries current I, so the total enclosed current is:

Ie=nLI

Substituting in Ampere's law:

BL=μ0nLI

Simplifying,

B=μ0nI

3. Interpretation

The magnetic field inside a long solenoid is directly proportional to both the current I and the number of turns per unit length n.

B=μ0nI

-

The field is uniform inside the solenoid.

-

It is independent of the radius or cross-sectional area.

-

The field is zero outside, based on symmetry and cancellation of contributions from opposing loops.

The right-hand rule determines the field direction: curl the fingers of your right hand around the solenoid in the direction of current flow, and the thumb points in the direction of the magnetic field inside.

4. Physical Meaning

This uniform field resembles that inside a bar magnet, where one end of the solenoid behaves like a north pole and the other as a south pole.

In practice, inserting a soft iron core enhances the field strength many times due to magnetic permeability, producing a strong electromagnet used in motors, speakers, and MRI systems.

The Toroid

1. Structure and Analogy

A toroid is a hollow circular ring around which wire is wound closely and uniformly, as shown in Fig. 3(a). It can be visualized as a solenoid bent into a circular shape so that its ends meet.

When a current I passes through the windings, magnetic field lines form concentric circles inside the toroidal core. Due to symmetry, the field is tangential at every point inside the core and confined within it.

Thus, a toroid is essentially a circular solenoid, and in its ideal form, it perfectly confines the magnetic field within its windings.

2. Magnetic Field Inside a Toroid

Let's derive the field using Ampere's law, similar to the solenoid.

Choose a circular Amperian loop of radius r centered at the toroid's axis, as in Fig. 3(b). The magnetic field B is tangent to this loop at all points, so:

∮B⋅dl=B(2πr)

The total current enclosed by this loop equals the current through all turns that lie within it:

Ie=NI

where N = total number of turns in the toroid.

Applying Ampere's law:

B(2πr)=μ0NI

Hence, the magnetic field at a distance r from the center is:

B=μ0NI/2πr

3. Nature of the Field

This expression shows that B varies inversely with r—it is stronger near the inner edge and weaker near the outer edge of the toroid.

However, for a tightly wound toroid where the difference between inner and outer radii is small, B may be considered uniform and equal to its value at the mean radius r=ravg.

4. Field in Different Regions

Refer to Fig. 3(b), which shows three circular Amperian loops:

-

Loop 1 (radius r1) lies inside the hollow center.

Ie=0⇒B1=0The magnetic field inside the hollow region is zero.

-

Loop 2 (radius r2) lies within the toroidal core.

Ie=NI⇒B2=μ0NI/2πr2The magnetic field inside the toroidal core is non-zero and tangential.

-

Loop 3 (radius r3) lies outside the toroid.

Ie=0⇒B3=0

The current entering and leaving the surface cancels, so:Thus, the field outside the toroid is zero.

Hence, the field exists only within the core, confined by symmetry.

Comparison of Solenoid and Toroid

To compare, express both results in the same form.

For a solenoid:

B=μ0nI

For a toroid:

B=μ0NI/2πr

But since N=2πrn (because 2πr is the circumference and n is turns per unit length),

B=μ0nI

Thus, the magnetic field inside a toroid is the same in form as that inside a solenoid.

| Property | Solenoid | Toroid |

|---|---|---|

| Shape | Cylindrical coil | Circular (ring-shaped) coil |

| Field inside | Uniform and along the axis | Tangential and confined to the core |

| Field outside | Almost zero | Exactly zero (ideal case) |

| Application | Electromagnets, relays, sensors | Inductors, transformers, magnetic storage |

Physical Interpretation and Practical Insights

1. Energy Concentration

Both solenoid and toroid are designed to concentrate magnetic energy in a defined region. In the solenoid, energy is stored uniformly in its core; in the toroid, it is stored completely within the circular path, minimizing external magnetic interference.

2. Minimizing Leakage Fields

The toroid is often preferred when magnetic field containment is essential. Since the field lines form closed loops inside the toroid, there is virtually no external field, reducing energy loss and electromagnetic interference.

In contrast, a solenoid's external field—though weak—still exists, making it less ideal in precision circuits.

3. Real vs. Ideal Behavior

In reality, a toroid's windings form a slight helical path, leading to a minimal external field. Similarly, finite solenoids deviate slightly from the perfect uniformity predicted by theory. However, for practical lengths (where L≫r), these deviations are negligible.

Derivation Recap

1. Solenoid

∮B⋅dl=μ0Ie

BL=μ0nLI

B=μ0nI

2. Toroid

∮B⋅dl=B(2πr)=μ0NI

B=μ0NI/2πr

and using N=2πrn,

B=μ0nI

Thus, both yield the same magnetic field expression under symmetric conditions.

Summary

-

A solenoid is a long helical coil producing a uniform magnetic field inside and nearly zero field outside.

-

A toroid is a solenoid bent into a circular ring, confining its field completely within the core.

-

Both obey Ampere's law, which simplifies field derivation under symmetry.

-

Inside both structures,

B=μ0nI -

Outside, the magnetic field is negligible (solenoid) or zero (toroid).

-

Inserting a magnetic core amplifies the field significantly, forming the principle behind electromagnets and inductors.

Example (Illustrative)

Example:

A long solenoid has 800 turns per meter carrying a current of 2.5 A. Find the magnetic field inside it.

Solution:

B=μ0nI=(4π×10−7)(800)(2.5)=2.51×10−3 T

Hence, the field inside the solenoid is 2.51 mT (millitesla).

Concluding Remarks

The study of solenoids and toroids showcases the elegance of Ampere's law in simplifying magnetic field problems with symmetry. Despite their structural differences, both devices produce predictable, controllable magnetic fields essential for modern electrical and electronic technology.

In essence:

-

The solenoid demonstrates how to create a uniform magnetic field over a region.

-

The toroid refines that concept to ensure perfect confinement of magnetic flux.

Together, they represent the practical heart of magnetostatics—bridging the gap between theoretical physics and real-world applications.