Introduction

We already know that a conductor that is carrying an electric current generates a magnetic field around it. This magnetic field has the Biot-Savart law, and the right-hand thumb rule can be used to determine the direction of the magnetic field. In addition, we also learn that an external magnetic field has a force on a conductor that carries current when it is placed in the magnetic field. The law of the Lorentz force is used to explain this magnetic interaction.

It can be logically deduced from these two notions that the placement of two current-carrying conductors close to one another will result in the generation of a magnetic field that will influence the other. Therefore, the two conductors have equal yet opposite magnetic forces on them.

The nature of these magnetic forces was investigated during the period 1820-1825 by the French physicist André-Marie Ampere, who formulated the basic relationship between current and magnetic interaction. The ampere, a unit of electric current, was defined in his precise experiments, and its definition was founded on the force between two parallel current-carrying wires.

In this blog, we shall learn the mechanism of the forces in detail, get the elucidation of the expression of the force between two parallel currents, and also comprehend how the phenomenon is the basis of the ampere.

Magnetic Field Due to a Long Straight Conductor

Consider a long straight conductor carrying a steady current Ia. According to Ampère’s circuital law, the magnetic field at a distance d from the conductor is given by:

Ba = μ0Ia/2πd

where

Ba = magnetic field due to conductor ‘a’,

μ0 = permeability of free space (4π×10−7 T m/A),

Ia = current in conductor ‘a’,

and d = perpendicular distance from the conductor.

The direction of this field can be determined by the right-hand rule: if the thumb of the right hand points in the direction of the current, then the curled fingers indicate the direction of the magnetic field around the conductor.

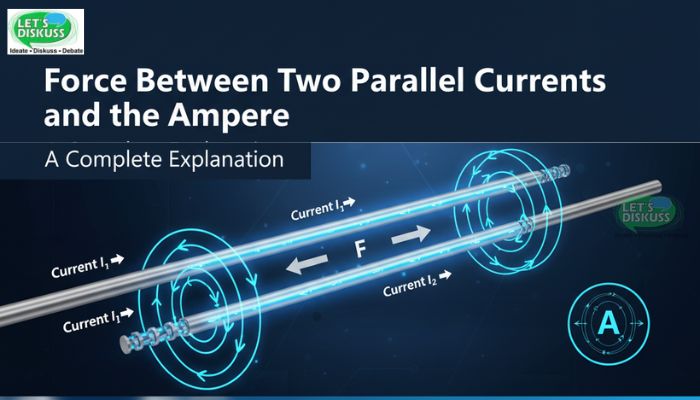

Description of the Setup (Refer to Fig.)

The figure shows two long, straight, parallel conductors labeled ‘a’ and ‘b’, carrying steady currents Ia and Ib, respectively. They are separated by a distance d. The magnetic field Ba is produced by conductor ‘a’ and acts at all points along the length of conductor ‘b’.

The direction of Ba, as given by the right-hand rule, is downward (when the conductors are placed horizontally as shown in the Figure).

Force on One Conductor Due to the Other

Let us now examine the force exerted by the magnetic field of conductor ‘a’ on conductor ‘b’.

The conductor ‘b’, carrying a current Ib, lies in the magnetic field Ba produced by ‘a’. The magnetic field exerts a Lorentz force on each charge moving through conductor ‘b’. The collective effect of this on the conductor as a whole produces a magnetic force given by:

Fba = IbLBasinθ

Here,

- Ib = current in conductor ‘b’

- L = length of the conductor segment considered

- Ba = magnetic field due to conductor ‘a’

- θ = angle between the current direction and the magnetic field

Since the conductors are parallel, the magnetic field Ba is perpendicular to the direction of current Ib. Hence, θ = 90° and sinθ = 1.

Therefore,

Fba = IbLBa

Substituting the expression for Ba:

Fba = IbL(μ0Ia/2πd)

Thus, the force on conductor ‘b’ due to ‘a’ is:

| Fba = μ0IaIbL/2πd |

Direction of the Force

The direction of the magnetic force is determined by the right-hand screw rule or the vector cross product F = I(L×B).

For the configuration shown in the Figure, the direction of Fba is towards conductor ‘a’. This means that conductor ‘b’ is attracted towards ‘a’.

Force on the First Conductor Due to the Second

According to Newton’s third law of motion, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Hence, conductor ‘a’ must also experience a magnetic force due to the field produced by conductor ‘b’.

By symmetry, the magnetic field produced by conductor ‘b’ at the location of ‘a’ is:

Bb = μ0Ib/2πd

Therefore, the force on a length L of conductor ‘a’ due to ‘b’ is:

Fab = IaLBb = μ0IaIbL/2πd

But the direction of this force is towards conductor ‘b’, opposite to Fba. Hence,

| Fab = −Fba |

This confirms that the two conductors exert equal and opposite forces on each other, perfectly consistent with Newton’s Third Law.

Nature of Interaction: Attraction and Repulsion

The direction of these forces depends on the directions of the currents in the two conductors.

- When currents are in the same direction:

The force on each conductor is attractive. Each wire pulls the other towards itself. - When currents are in opposite directions:

The force becomes repulsive. Each wire pushes the other away.

Thus, we can summarize:

| Parallel currents attract, and antiparallel currents repel. |

This rule is the opposite as opposed to electrostatic interactions, wherein the same charges repel and the opposite charges attract. The same cannot be said about magnetostatic systems, though: electric currents on two conductors attract each other, which is due to the magnetic forces created by the movement of charges and the resulting magnetic fields.

Force Per Unit Length Between Two Conductors

It is often more convenient to express this magnetic interaction in terms of the force per unit length between the conductors, as the total force depends on the length of the wires considered.

Let fba represent the force per unit length on conductor ‘b’ due to ‘a’. Then,

fba = Fba/L = μ0IaIb/2πd

Similarly,

fab = μ0IaIb/2πd

Hence, the magnitude of the force per unit length between two long parallel conductors separated by a distance d, carrying currents Ia and Ib, is given by:

| f = μ0IaIb/2πd |

Factors Affecting the Force

- Magnitude of the currents (Ia, Ib) – The force increases with larger currents.

- Distance between the conductors (d) – The force decreases as the distance increases.

- Medium between the conductors – The force depends on the magnetic permeability μ of the medium; it is maximum in vacuum where μ = μ0.

Definition of the Ampere

The phenomenon of force between two parallel currents provides a fundamental basis for the definition of the ampere, which is one of the seven SI base units.

1. Formal Definition

The ampere is defined as:

“That constant current which, if maintained in two straight parallel conductors of infinite length and negligible cross-section, placed one metre apart in vacuum, would produce between them a force of 2×10−7 N per metre of length.”

This definition was adopted internationally in 1946 by the International Committee on Weights and Measures (CIPM).

2. Derivation from the Force Formula

From the expression for force per unit length:

f = μ0IaIb/2πd

If Ia = Ib = 1 A and d = 1 m,

f = 4π×10−7×1×1/2π×1 = 2×10−7 N/m

Hence, one ampere is that current which produces this force when the above conditions are satisfied.

3. Significance of the Definition

- The definition of the ampere links mechanical force and electromagnetism.

- It provides a reproducible and measurable method for defining current.

- A device called the current balance was used to measure this force accurately in laboratory settings.

- In modern metrology, this mechanical definition has been replaced by a definition based on the elementary charge (since 2019), but Ampère’s classical definition remains of great theoretical importance.

Relation Between the Ampere and the Coulomb

The ampere and the coulomb are closely related units in the SI system.

Since electric current is the rate of flow of charge, we have:

I = Q/t

where Q is the charge passing through a cross-section in time t.

If a steady current of 1 A flows through a conductor for 1 s, the charge transported is:

Q = I×t = 1×1 = 1 Coulomb

Thus,

| 1 C = 1 A×1 s |

This relationship connects the mechanical definition of the ampere with the electrostatic unit of charge.

Experimental Verification and Ampère’s Contribution

In 1820-1825, the systematic series of experiments done by Andre-Marie Ampere using the dainty torsion balances studied the interaction of current-bearing conductors. He measured the forces between the wires that had constant currents and found that they complied with the pattern of the theoretical analysis.

His observations determined two precepts:

- Currents in the same direction attract each other.

- Currents in opposite directions repel each other.

These observations proved the accuracy of the Biot-Savart law and the law of Lorentz force, in addition to the preparation of the quantitative definition of the electric current.

The work of Ampere brought together the science of electricity and magnetism, and he was often known as the "Father of Electrodynamics".

Applications and Practical Implications

This is the magnetic force that develops between currents running parallel; although it is of small scale, it is an essential phenomenon in many electrical and electromagnetic systems:

- Power Transmission Lines:

Long transmission cables with large currents are exposed to mutual electromagnetic forces, which may cause displacement or vibration, specifically in a fault condition like a short circuit. - Electric Motors and Generators:

The interplay of current-carrying conductors and magnetic fields is the key to the design of electric motors in which the windings are under the influence of the Lorentz force to produce mechanical motion. - Electromagnets and Coils:

The forces between adjacent turns are either attractive or repulsive and determine the mechanical stability of the assembly in small-diameter coils. - Current Balances:

Mechanical force devices that make use of this force to measure current comparatively base themselves on comparison of the resultant mechanical force to well-characterised reference standards.

Numerical Example

Example:

Two long parallel wires are separated by 0.05 m and carry currents of 10 A each in the same direction. Calculate the force per metre length between them.

Solution:

f = μ0IaIb/2πd

f = 4π×10−7×10×10/2π×0.05

f = 2×10−3 N/m

Hence, each wire experiences a force of 2 mN per metre, directed towards the other wire (attraction).

Summary and Key Takeaways

The interaction between two parallel, current-carrying conductors can be studied to uncover the very deep relationship existing between electricity and magnetism. The relationship can be summarised in a number of quantitative statements.

- The magnetic field of a long, straight conductor with a current, that is, carrying a current of the form I, is equal to.

B = μ0I/2πd - Force between two parallel conductors:

F = μ0IaIbL/2πd - Force per unit length:

f = μ0IaIb/2πd - Parallel currents attract, antiparallel currents repel.

- The definition of 1 ampere is based on a force of 2×10−7 N/m between two 1-metre apart wires carrying 1 ampere each.

- The ampere and the coulomb are related by 1 C = 1 A×1 s.

The detailed studies of the ampere formed the basis of the modern electromagnetic theory, and the ampere has become one of the basic SI base units.