Introduction

One of the most interesting properties of matter is magnetism. Since the basic compass that points towards the geomagnetic north to the advanced magnetic storage gadgets in the current computing devices, the relationship between matter and magnetic field has had significant impact on the newer technological advancement. However, not every substance would react to applied magnetic fields identically, some are repelled by the fields, others weakly attracted, and a small percentage would display strong magnetic behavior.

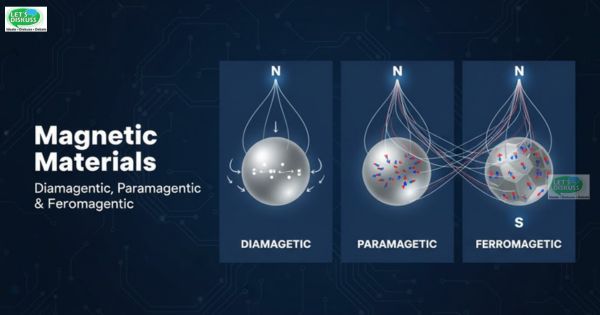

Physically, these responses are systematically grouped into diamagnetic, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials. The primary parameter that forms the basis of this classification is a physical parameter referred to as the magnetic susceptibility ( χ ) that measures the degree to which a material gets magnetized when it is subjected to an external magnetic field.

Understanding Magnetic Susceptibility

Magnetic susceptibility is the quantity of how strongly the material will be magnetized when placed within an external magnetic field. Mathematically, it is the ratio of the magnetization M (the magnetic moment per unit volume) to the applied magnetic field H:

χ = M/H

-

At negative value, χ, the material will be diamagnetic and will be repulsed by the magnetic field.

-

When the χ is small and positive, the material is said to be paramagnetic which means that it is weakly attracted to the field.

-

On the other hand, χ is a large and positive value of if means that it is ferromagnetic, meaning that the material is highly attracted.

Table 1 presented in the reference material is a summary of the general properties of these three types.

| Type | Magnetic Susceptibility (χ) | Relative Permeability (μ) | Magnetic Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diamagnetic | −1 ≤ χ < 0 | μ < μ₀ | Weakly repelled |

| Paramagnetic | 0 < χ < ε | μ > μ₀ | Weakly attracted |

| Ferromagnetic | χ ≫ 1 | μ ≫ μ₀ | Strongly attracted |

Diamagnetism — The Subtle Repulsion

The most common but the weakest type of magnetic interaction is the phenomenon of diamagnetism. It is found inside of all matter, but the magnitude of it is usually so insignificant that it is obscured by other more powerful phenomena like paramagnetism or ferromagnetism.

1. The Origin of Diamagnetism

The magnetic field of electrons is the result of the electrons being in an orbital motion around the nucleus. When the magnetic field is impregnated externally, it causes a minor adjustment of this orbital motion. The resulting change produces a magnetic moment which is opposite in polarity to the applied field.

As a result, diamagnetic substances oppose the applied magnetic field, creating a weak repulsive effect. This phenomenon is beautifully explained by Lenz's law, which states that the induced current always opposes the change that caused it.

2. Behavior of Diamagnetic Materials

The relationships between the magnetic field lines and a diamagnetic substance have been illustrated in Figure 1(a). The field lines are drawn away, and they become less concentrated in the material, meaning that internal magnetic field is less in the presence of an external field.

A conventional magnet, when placed in a non-uniform magnetic field, will move to higher field strengths areas and move to lower field strengths areas thus moving against the direction of a conventional magnet.

3. Examples and Special Cases

Common diamagnetic materials include:

-

Bismuth

-

Copper

-

Lead

-

Silicon

-

Water and nitrogen (at STP)

The diamagnetic effect is generally very weak — often only one part in 10⁵. However, an extraordinary case occurs in superconductors.

4. Superconductors: Perfect Diamagnetism

At very low temperatures, certain metals like mercury and lead become superconductors. In this state, they exhibit perfect diamagnetism — meaning they completely expel magnetic fields. For a perfect diamagnet,

χ = −1 and μ = 0

This phenomenon, called the Meissner effect, allows superconductors to levitate magnets and has remarkable applications in magnetic levitation trains and frictionless bearings.

Paramagnetism — Mild Attraction

The next degree of magnetic phenomena is paramagnetism. There is a low tendency of such materials being attracted by external magnetic fields, and the magnetic moments of such materials rotate slightly along these field directions.

1. Microscopic Origin

The atoms or ions in a paramagnetic material have permanent magnetic dipole moments (that is, due to the existence of unpaired electrons in atomic orbitals). When an applied magnetic field is not present, these dipoles will be randomly oriented due to constant thermal agitation, and the net magnetization will be zero.

When an outside magnetic field (B₀) is applied, the dipoles align with this field with preference thus producing a net magnetization perpendicular to the field direction. This improvement is shown in Figure 1(b) - the field lines have been more thickened into the material.

2. Behavior and Temperature Dependence

The paramagnetic materials start to become more and more magnetized as the strength of the applied field increases but it decreases with temperature. This is inversely related to the fact that the alignment of the magnetic dipoles is disrupted due to the thermal agitation.

This relationship is described by Curie's Law:

M = CB₀/T

or equivalently,

χ = Cμ₀/T

where C is Curie's constant and T is the absolute temperature.

Thus, the magnetic susceptibility χ of a paramagnet is inversely proportional to temperature — as the temperature rises, magnetization decreases.

3. Examples of Paramagnetic Materials

Typical examples include:

-

Aluminum

-

Sodium

-

Calcium

-

Oxygen (at STP)

-

Copper chloride

These materials exhibit only a slight enhancement of the magnetic field within them — typically one part in 10⁵.

Ferromagnetism — Strong and Permanent Magnetism

Ferromagnetic materials have the strongest characteristics of all the magnetic materials. They exhibit spontaneous and strong magnetization without the presence of external magnetic field, as is the case with iron, cobalt and nickel.

1. The Domain Theory

In ferromagnet materials, the atoms also have permanent magnetic dipole moment similar to paramagnets, however, they exhibit a strong cooperative effect. In the microscopic regions called domains, the atoms form groups which randomly match the way their dipoles are oriented.

The domains serve as miniature magnets that consist of about 10¹¹ atoms. Without the external magnetic field, such domains will be randomly oriented (see Figure 2(a)) and therefore, the magnetic moments of such domains will cancel each other and the bulk material will be effectively unmagnetized.

When an external magnetic field B₀ is applied, the domains gradually align themselves with the direction of the field (Figure 2(b)) to give a strong macroscopic magnetization of the material.

2. Hard and Soft Ferromagnetic Materials

Ferromagnetic materials are classified as:

-

Hard ferromagnets: Retain their magnetization even after the external field is removed. Examples: steel, alnico (alloy of aluminum, nickel, cobalt).

-

Soft ferromagnets: Easily magnetized and demagnetized. Examples: soft iron, used in transformer cores.

3. Curie Temperature and Phase Transition

At high temperatures, the thermal motion of atoms disrupts domain alignment. Above a critical temperature called the Curie temperature (Tc), the ferromagnet loses its permanent magnetism and becomes paramagnetic.

The susceptibility in the paramagnetic region (above Tc) is given by:

χ = C/(T - Tc) × (T > Tc)

Table 2 lists the Curie temperatures of some common ferromagnetic materials:

| Material | Curie Temperature (Tc in K) |

|---|---|

| Cobalt | 1394 |

| Iron | 1043 |

| Fe2O3 | 893 |

| Nickel | 631 |

| Gadolinium | 317 |

This temperature-dependent behavior of ferromagnets reminds us of the melting of a solid — a gradual transition from order (ferromagnetic) to disorder (paramagnetic).

Example: Estimating Magnetization in Ferromagnetic Iron

In order to get the idea of the magnitude of magnetization, it is good to refer to the example of 5.11 in the reference matter.

A cubic domain of iron, whose side length is 1 μm is considered in this study. The count of atoms in this domain, together with the resultant magnetization is calculated in the following:

Step 1: Volume and Mass of the Domain

V = (10−6 m)3 = 10−18 m3

Given the density of iron, ρ = 7.9 g/cm³ = 7.9 × 10³ kg/m³,

the mass of the domain is

m = ρV = 7.9 × 103 × 10−18 = 7.9 × 10−15 kg

Step 2: Number of Atoms

Molecular mass of iron = 55 g/mol = 0.055 kg/mol.

Avogadro's number, Na = 6.023 × 10²³ atoms/mol.

N = mNa/M = (7.9 × 10−15 × 6.023 × 1023)/0.055 ≈ 8.65 × 1010 atoms

Step 3: Magnetic Moment and Magnetization

Magnetic moment per atom = 9.27 × 10⁻²⁴ A·m².

If all atomic moments align perfectly:

mmax = N × 9.27 × 10−24 ≈ 8.0 × 10−13 A·m2

and

M = mmax/V = (8.0 × 10−13)/(10−18) = 8.0 × 105 A/m

Thus, the maximum magnetization of iron can reach around 8 × 10⁵ A/m, showing just how intense ferromagnetic alignment can be.

The Hysteresis Effect

The relationship between magnetic field B and magnetizing force H in ferromagnetic materials is non-linear and depends on the material's magnetic history. This is known as magnetic hysteresis.

1. Understanding the B-H Curve

Figure 3 illustrates a typical B-H hysteresis loop:

-

Starting with an unmagnetized sample, increasing H increases B up to a point where further increase produces little effect — this saturation region corresponds to curve Oa.

-

When H is reduced to zero, B doesn't return to zero. The residual magnetism at this point is called retentivity (Br).

-

To demagnetize the sample, a reverse field must be applied. The field required to reduce B to zero is known as coercivity (Hc).

In Figure 3, for example, Br ≈ 1.2 T and Hc ≈ 90 A/m.

2. Physical Meaning of Hysteresis

The hysteresis loop represents the lag between magnetization and the applied field due to the realignment of domains. Each cycle of magnetization involves energy loss — shown as the area enclosed by the loop — which manifests as heat in the material.

3. Applications of Hysteresis

-

Soft magnetic materials with narrow hysteresis loops are ideal for transformers (low energy loss).

-

Hard magnetic materials with wide loops are used for permanent magnets (high retentivity and coercivity).

Comparing the Three Types of Magnetic Materials

Let's now summarize the key differences between diamagnetic, paramagnetic, and ferromagnetic materials:

| Property | Diamagnetic | Paramagnetic | Ferromagnetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptibility (χ) | −1 ≤ χ < 0 | 0 < χ < ε | χ ≫ 1 |

| Relative Permeability (μ) | μ < μ₀ | μ > μ₀ | μ ≫ μ₀ |

| Direction of Magnetization | Opposite to field | Along the field | Strongly along field |

| Dependence on Temperature | Independent | Decreases with T | Disappears above Tc |

| Examples | Bismuth, Copper, Lead | Aluminum, Sodium | Iron, Nickel, Cobalt |

Applications and Real-World Importance

Magnetic substances are important in a myriad of applications in industries:

1. Diamagnetic Materials

Magnetic levitation (MagLev) trains use superconductors (perfect diamagnets) and are propelled by trains being repelled by magnets, without the use of friction.

2. Paramagnetic Materials

Paramagnetic materials are also used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in oxygen measurements, and in other cryogenic studies; in all of these applications, the small magnetization makes the measurements of the paramagnet very specific.

3. Ferromagnetic Materials

Almost all magnetic technologies (such as electric motors, transformers, and generators) and data storage devices, as well as magnetic compasses, are based on ferromagnetic materials.

Conclusion

The world of magnetic materials has become the exemplar of the astonishing interaction of atomic structure with the emergent macroscopic behavior, ranging in strength between weakly repelling diamagnets to strongly attracting ferromagnets.

Diamagnetism, which is faint, explains the effect of induced electrons movement; paramagnetism, which reveals an aspect of the temperature dependence of magnetic alignment, and ferromagnetism which is the strongest of the magnetic phenomena explains how the concerted action of atoms produces a stronger and lasting magnetic interpretation.

With the advance of modern physics and materials science, understanding of these magnetic properties will always spur technological change, such as superconducting levitation, nanomagnetic data storage, and so on, to show that even the smallest atomic spins can form the basis of future achievements.